Supporting the real economy, SME financing, securitisation and ESN

The European awakening

Europe’s postwar model, anchored in the imperative of the continent’s reconstruction, offered social security, industrial strength, a harmonised legal and regulatory setting, while delivering prosperity and political stability, for decades. However, its heavy structures – suited to an era of slower change and national economies – are now coming under pressure from intensifying demographic trends, productivity languishing for years under the weight of an increasingly complex legal environment, and a shifting global order calling for a more competitive and self-reliant Europe.

Regarding competitiveness, concerns are not new, as business leaders have long warned of underinvestment, slow digital adoption, stringent ESG requirements, and declining industrial resilience. However, the publica- tion of flagship reports by Mario Draghi, Enrico Letta, and Christian Noyer, led Brussels to officially frame this stagnation as a strategic emergency1. Mario Draghi in particular is adamant on the negative impact of the regulatory context as it stands.2

European defence, for decades reliant on NATO to which U.S. is the central contributor, and therefore long treated as a marginal budget line, is now seen as a matter of sovereignty.3 Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine was a wake-up call, but the deeper strategic rupture emerged from Washington. Europe’s longstanding reli- ance on U.S. military power, once a given, turned a liability, especially under the renewed scepticism of NATO, which president Donald Trump brought from his first mandate.

The political response is converging. Then Chancellor Olaf Scholz and President Emmanuel Macron have called for a European defence-industrial base to match the continent’s strategic weight. Already back in 2021, then NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg summed up the shift: “It is not only about spending more. It is also about doing so together.”3

On the regulatory front, the Omnibus package, launched in March 2025, aims to boost competitiveness with proposals for simplification in fields like sustainable finance reporting, sustainability due diligence, EU Taxonomy, carbon border adjustment mechanism, and European investment programmes, which shall “reduce complexity of EU requirements for all businesses, notably SMEs and small mid-caps […], while still enabling companies to access sustainable finance for their clean transition”4.

However, regulatory streamlining is not enough. In contrast to the U.S., where capital markets dominate, Europe remains a bank-financed economy – especially for SMEs. As a response, the Capital Markets Union developed into the broader Savings and Investments Union (SIU), with a more holistic approach encompassing the entire EU financial system, whereby capital markets and the banking sector together will enhance the efficient channelling of savings into investments5. Securitisation, with its legal framework currently under review, plays a role in placing traditional bank loans’ underlying risk with capital market investors.

The creation of a business-friendly environment is crucial. The scale of required investments for the deploy- ment of this new and enhanced industrial capacity it’s hardly achievable without the private sector, financed by both the capital markets and the European banking sector.

That is why the attention is turning to Europe’s industrial backbone: its SMEs. Taking the defence sector for example, in the Joint White Paper on European Defence Readiness 2030, the European Commission identifies SMEs as key providers of innovation and agility in defence technologies. The €7.3 billion European Defence Fund (EDF) for 2021–27 explicitly supports SME participation, with up to €840 million estimated to be allotted for the 2023–2027 period. Already, more than 2,500 SMEs are embedded in Europe’s defence supply chains6. But more broadly, meeting the EU’s competitiveness, energy, and defence ambitions will require an estimated €500 billion in additional annual investment7. This is a political and institutional challenge that will define Europe’s future.

In the next two sections, we will examine how Europe might begin to close this gap: first, by understanding the needs and potential of SME financing; and second, by retooling its financial infrastructure through instruments like European Secured Notes (ESNs) and securitisation technology – so that European loans and savings can be converted into European investments, growth and prosperity.

Trends in firms financing

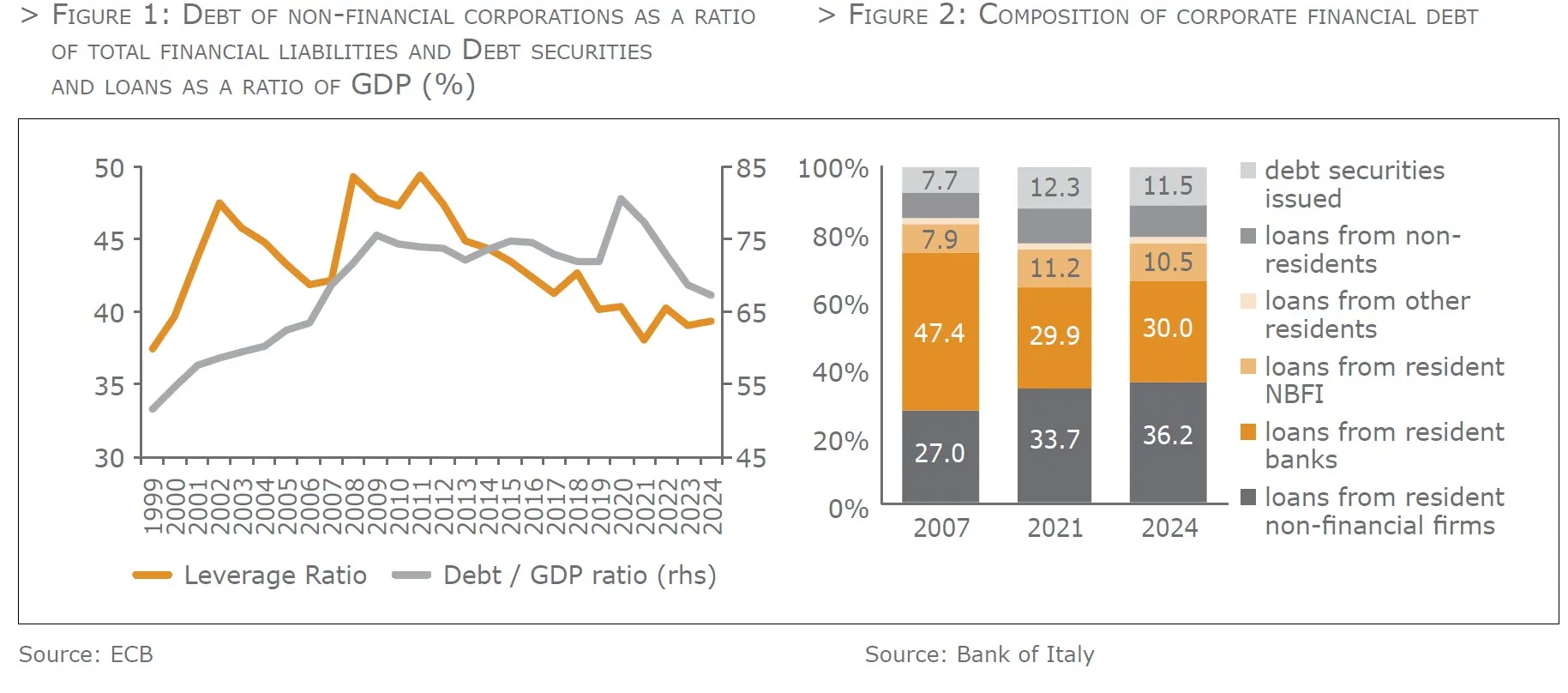

European firms, small and medium-sized companies in particular, still rely significantly on bank lending, despite recent increases in the issuance of corporate securities and credit sourced from other financial intermediaries. However, since the Great Financial Crisis, the financial structure of companies has strengthened considerably. Leverage has fallen from 49.4% in 2008 to 36.4% in 2024 for non-financial companies in the euro area, thanks in part to their stronger capitalisation. In addition, the composition of financial debt has changed: the share of bonds, between 2007 and 2024, has grown from 7.7% to 11.5% of total financial debt; bank financing has declined, from 47% in 2007 to 30% in 2024, while debt exposure with non-bank intermediaries (from 7.9% to 10.5%) and with foreign financing sources has increased.

At the individual company level, bank credit and market financing generally coexist. Indeed, it is rare for euro area firms to fund themselves exclusively via financial markets. Roughly 22% of euro area firms with more than 20 employees tap the bond market, besides obtaining bank loans. In this regard, a recent ECB study8 found that firms with bank funding are generally less productive than competitors which do not rely on bank loans as a source of external financing. This result is consistent with the objectives of the Savings and Investments Union (SIU), as a more diversified funding structure could potentially enhance the productivity of euro area firms.

SMEs have also seen a change in their financial structure in recent years. In particular, in the context of the global increase in non-bank financing, a market for debt securities for new and small issuers in the euro area is developing. A recent study9, focused on firms entering the bond market for the first time on or after 2010, found that most new issuers are significantly smaller than historical issuers, consist of private firms, and lack a credit rating from a large rating agency. This market appears to be more like a private debt market than a traditional bond market and seems to be drawing relatively more from the pool of traditional bank borrowers. However, according to the results of the study, there is evidence that new issuers tend to substitute only a part of their bank loans with bonds. In conclusion, banking intermediaries are still important for small and new issuers, and this blurs the conventional dichotomy between intermediated and market financing.

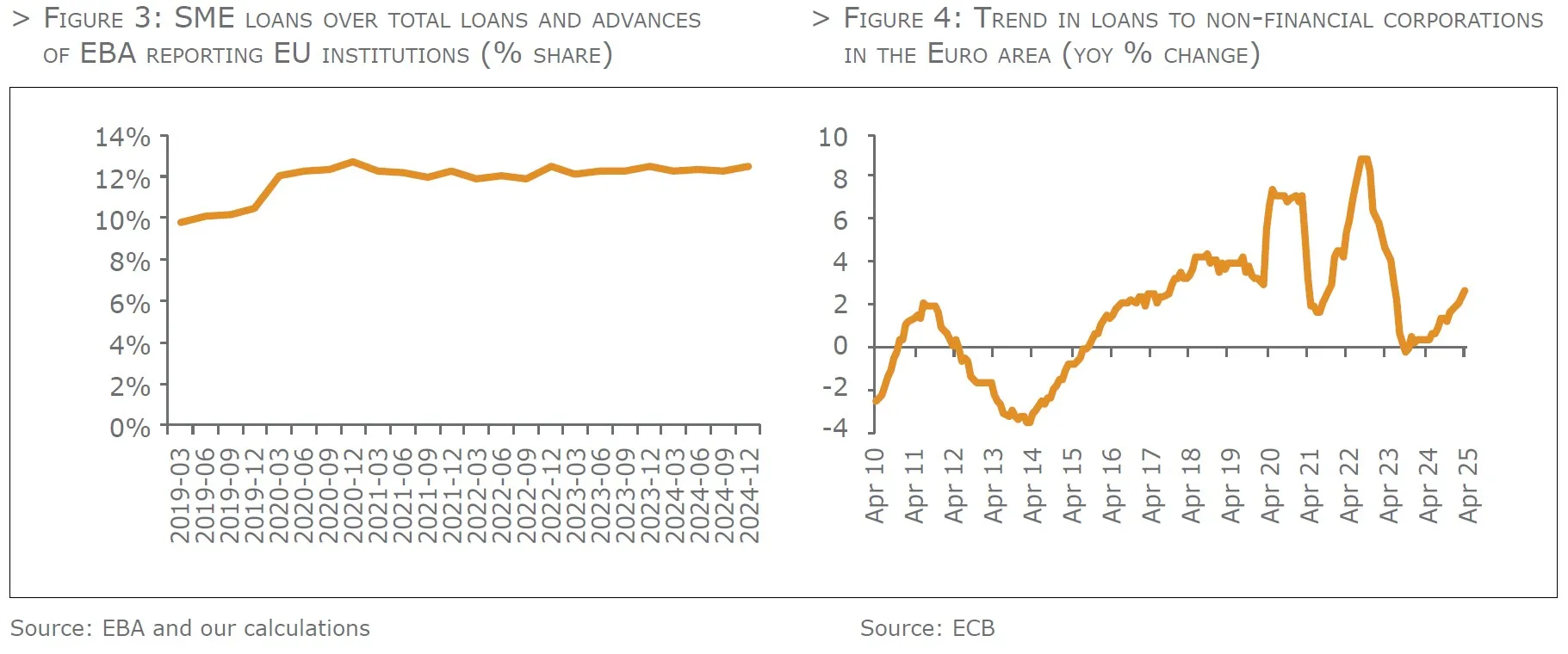

At the end of 2024, loans to SMEs accounted for around 12.5% of total loans and advances of banks in the European Union (based on the sample of EBA’s Largest Reporting Institutions). This share has remained broadly stable since the outbreak of the pandemic, whereas in 2019 it was around 10%. This could reflect the fact that most of the public intervention schemes announced at the early stages of the pandemic were in fact targeted at SMEs.

Alongside the structural changes already briefly mentioned, the evolution of lending to businesses has recently been influenced by the great geopolitical uncertainty that is holding back fixed investment. In 2024, bank lending to businesses remained weak due to still tight credit conditions and low credit demand, while show- ing signs of recovery since the second half of 2024. Bank lending to firms strengthened gradually in the first months of 2025, growing at an annual rate of 2.6% in April after 1.7% in December 2024, while corporate bond issuance was subdued. Lending to small firms continued to decline, falling by 2.1% in April, a trend that has been ongoing since mid-2021. Surveys of banks and businesses showed an improvement in lending conditions, implemented through lower interest rates. However, credit demand from companies remained weak, mainly due to sufficient internal funds to finance their business plans, such that the share of firms applying for bank loans remained relatively low. This pattern was consistent across company sizes, with a higher percentage of large firms (35%) reporting applications for bank loans compared to SMEs (18%)10.

Securitisation and esn as viable financial tools: how to strike the right balance

In this section we will address the refinancing of SME bank credit portfolios (SME assets) through comple- mentary financial technologies and instruments, exploring the differences and the characteristics of both SME securitisation and European Secured Notes (as referred to in the Covered Bond Directive (CBD), meaning a dual recourse funding instrument collateralized by SME assets and regulated by a specific EU legal framework).

Our intention is to demonstrate that these instruments are indeed compatible and complementary and align with the objectives of the SIU. As will be clear in the following paragraphs, securitisation is typically a tool fit for regulatory capital management and for the refinancing of certain categories of assets, whereas ESN is much more cost-efficient and best suited to be a pure funding instrument.

a) Peculiarity of SME assets and their treatment in structured finance transactions

SME assets typically have a short to medium maturity (compared, for instance, to mortgages), and therefore need refinancing at a higher pace. In securitisation, issued notes repayment follows the amortization of the underlying portfolio. Therefore, in order to obtain a longer tenor on the notes, the portfolio needs a pre-defined replenishment period, when expiring assets are replaced with new ones, thus extending the amortization period of the collateral portfolio.

Typically, in a securitisation the characteristics of the replacement assets are set in advance in order to ensure asset quality throughout the life of the transaction. The reason for adopting stringent criteria is the limited recourse nature of the issuance itself: the only claim investors have is represented by the securitised portfolio, therefore its evolving composition needs to follow strict criteria to avoid its deterioration as the sole source of proceeds to repay the notes.

Conversely, in a dual recourse transaction, like a covered bond – which ESNs aim to replicate – that feature, even if broadly inscribed in specific legislation and regulation, is somehow softened. This is because (i) bonds are issued in the context of a programme, where its segregated portfolio (cover pool) must cover all issued notes, at all times (coverage requirement); (ii) the credit quality of the cover pool is managed dynamically by the issuer, adjusting the overcollateralization (OC) levels in order to ensure adequate protection and also excluding non-performing receivables from the portfolio, thus ensuring the coverage requirement is continu- ously met by performing assets (this is not the case in securitisation); (iii) investors enjoy a first recourse on the issuer and, in case of issuer insolvency, or other contractual events, they have exclusive recourse over the cover pool; (iv) repayment of the bonds is typically through either bullet or soft bullet structures, instead of the amortising notes typical of securitisations.

According to the Covered Bond Directive the cover pool must be continuously adequate and cover principal, interest, and ongoing expenses. The eligibility criteria for replenishing assets mirror the initial collateral quality but allow more flexibility than securitisations.

Why are these features important? From a financial perspective, conditions evolve over the years and, for example, the interest accruing on the bonds may also increase or decrease over time. It is therefore essential to ensure the overall coverage of the interest payments on the bonds by the interest accruing on the evolving cover pool.

From a business perspective, the terms, sectors, and geographic distribution of SME loans may also change according to the bank’s commercial strategies. The issuance programme therefore ensures portfolio quality over time while allowing certain features to be adapted. This is critical for providing long-term funding stabil- ity to the issuer. Once set up, and as long as sufficient collateral exists, the issuer can issue notes based on market opportunities and funding strategy.

On the contrary, securitisations are bespoke transactions, typically structured for a single issuance. For the SME sector this difference is crucial, and it is clear dual-recourse funding instruments would enable refinancing the issuer’s SME portfolio for longer periods of time, irrespective of changes in general financial conditions, or of how the issuer’s origination business evolves. On the other hand, once certain conditions are met, securitisation allows the originating bank to free up regulatory capital, as well as meeting different risk appetites through the issuance of senior and more subordinated tranches. Securitisation is also an efficient way to refinance less standard SME loans, whereas ESN, acting as a programme on larger volumes of collateral assets, may favour more standardised SME portfolios.

In sum the two instruments – securitisation and ESN – are highly complementary and may both be used according to the objectives of the issuing bank and the respective market access windows.

b) requirements of the Securitisation Regulation

The Securitisation legislative package (a specific Regulation complemented by the CRR prudential provisions) was published in 2019. The goal of its current review is to simplify the framework by removing unnecessary burdens that do not enhance product robustness and have so far hindered the securitisation market’s recovery since the Great Financial Crisis11. Over time, EU institutions have promoted securitisation to help develop the Capital Markets Union, encourage risk sharing through financial markets, and support financing for the real economy.

There are a couple of aspects worth mentioning on the treatment of SME securitisations. So far, such transac- tions have represented a small percentage of all traditional (funded or “cash”) securitisation issuances, where the main asset class are residential mortgage-backed securities. Indeed, rather complicated regulatory require- ments have so far discouraged the execution of funded SME securitisations12.

On the contrary SMEs are one of the main asset classes used for synthetic securitisations, where typically originators keep the assets on their balance sheet and only sell part of the risk to specialised investors. Syn- thetic SME deals have proven to be an excellent means for financial institutions to manage their credit risk and capital needs, while promoting the participation of market players interested in investing in SME exposures13.

c) what role for ESN? And for securitisation?

An instrument governed by specific EU legislation and building on the dual recourse features would appeal to both issuers and investors, with the dual protection conferring comfort to certain categories of investors, while allowing banks to issue lower risk bonds at spreads way lower than those expected for a securitisation deal or even for unsecured senior bond issuances. Let us briefly explore the motivations for issuers and investors.

ESN, as a pure funding instrument, would afford the bank time flexibility according to market opportunities (as do traditional covered bonds in the mortgage credit space), building on the ability of a dual recourse instrument to mitigate volatility in financial markets. In addition, ESN would allow adapting certain collateral characteristics over time, while preserving its overall main criteria and quality. Finally, it is important to mention that covered bond programmes require dedicated internal structures and specific control functions – entailing structural and running costs – and a constant dialogue with supervisors. This is the reason why, in most countries, issuers are larger institutions. ESN would be subject to much of these features and conditions.

| ESN | SME securitisation | |

|---|---|---|

| Investor Security | dual recourse | recourse limited to the collateral portfolio |

| Cover SME Assets Suitability | for standard loans | for non-standard, alternative, more complex credit facilities |

| Bank CapitalRelief Suitability | no | yes |

| Funding Cost/ Investor Return | lower | higher |

| Investor Diversification | lower – single tranche | higher – multiple tranches with distinct risk profiles |

| Adaptability to bank’sloan asset origination policies | higher – more principle-based asset eligibility | lower – stricter eligibility criteria |

On the other hand, banks wishing to achieve both funding and capital relief for their SME portfolio may also use securitisation (traditional or synthetic), through bespoke transactions. Securitisations may be executed by banks under specific circumstances to refinance specific portfolios. They are one-off transactions where costs are primarily incurred at inception. For small portfolios (and often small institutions), securitisations are more widely used, notwithstanding the higher yield on the notes typically demanded by investors. Plus, less standard credit assets are likely to be more efficiently financed through securitisation.

Investors are bound by their specific guidelines and their risk-reward appetite. Therefore, those investors focus- ing on dual recourse instruments would evaluate the issuer’s strength and the analysis of the collateral would matter only for the recourse in case of issuer-related event of default. Investors specialized in securitisation, on the contrary, would focus on the collateral and on the structural features of the transaction, evaluating the specific risks embedded in the relevant transaction.

d) concrete examples of SME dual recourse transactions on the market and the way forward

Large banks financing SMEs are exploring all available tools to fund their portfolios, especially after the phase- out of the ECB’s TLTROs, which supported lending for years. Synthetic securitisations already provide capital relief and allow new lending within existing capital, but also this instrument needs regulatory updates to unlock its full potential.

Although no dedicated EU legislation exists yet, some dual recourse transactions backed by SME portfolios have recently entered the market14, receiving public rating by major ECAIs. These deals demonstrate strong interest from issuers and certain investors in innovative SME-backed structures. We estimate that new transactions would increase significantly if tailored legislation for ESN were introduced15.

Conclusion

As outlined in the first part, the EU’s vast needs for investments and innovation are crucial to maintaining com- petitiveness and strategic autonomy. The Union’s advancements in decarbonisation and overall sustainability will further bolster its global leadership. Achieving these objectives relies significantly on the private sector’s role in financing, channeling private savings, and providing expertise and best practices.

SMEs are strategic due to their capacity for flexibility and innovation in international markets. The gradual extension of ESG targets to SMEs enables them to contribute to the transition while retaining agility. For instance, the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive’s goals for buildings require financial backing from both banks, and SMEs leading the retrofitting efforts.

So, despite SMEs’ lower loan financing needs resulting from their current high liquidity and improved access to capital markets, the banking sector remains crucial for supporting their investments and innovation initiatives, and we encourage policymakers to introduce all necessary reforms in EU banking and financial markets regulation.

Initiatives like fostering SMEs’ capital bases, promoting IPOs, boosting private equity, and directing private savings toward investments are essential. Yet, for SMEs in general and especially micro enterprises, bank credit is still a crucial tool, as direct capital market participation remains challenging. Thus, accessible and cost-efficient bank funding is vital, with ESNs and securitisation playing a complementary role in restoring EU competitiveness.

By Elisa Coletti, Intesa Sanpaolo, Claudio Domingues, Millenium BPC, Per Anders Öjar Törnqvist, Danske Bank A/S and Stefano Patruno, Chairman of the ECBC, Moderator of the ECBC

European Secured Notes (ESN) Task Force, Intesa Sanpaolo

- Mario Draghi, Future of European Competitiveness, European Commission, September 2024; Enrico Letta, Much more than a market, European Commission, April 2024; Christian Noyer, Developing European Capital Markets to Finance the Future - Proposals for a Savings and Investments Union, report for French Prime Minister, April 2024.

- “But innovation is blocked at the next stage: we are failing to translate innovation into commercialisation, and innovative companies that want to scale up in Europe are hindered at every stage by inconsistent and restrictive regulations.” (Mario Draghi in “Future of European Competi- tiveness”).

- Jens Stoltenberg, Speech by NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg at the 67th Annual Session of the NATO Parliamentary Assembly; Olaf Scholz and Emmanuel Macron, remarks at the Munich Security Conference, February 2024.

- European Commission, Omnibus package for regulatory simplification, February 2025. “Commission simplifies rules on sustainability and EU investments, delivering over €6 billion in administrative relief” (Press Release, 26 February 2025).

- “Questions and answers on the Savings and Investments Union” (March 2025).

- European Commission, Joint White Paper on ReArm Europe Plan/Readiness 2030, April 2024.

- Estimates from European Investment Bank and European Commission, cited in Draghi Report (2024) and EIB Investment Report 2023–24.

- Desislava Andreeva et al, Low firm productivity: the role of finance and the implications for financial stability, ECB, Financial Stability Review, November 2024.

- Olivier Darmouni, Melina Papoutsi, May 2022, Non-bank lending to mid-size firms in Europe: evidence from corporate securities, ECB, Working paper.

- Source: Survey on the Access to Finance of Enterprises in the euro area, First quarter of 2025, ECB, April 2025.

- According to AFME statistics, European issuances amount globally to EUR244.9 bn at the end of 2024, whereas amounts issued were still higher just after the GFC (eg. €376.8 bn in 2011 – all figures including UK), AFME, Association for Financial Markets in Europe).

- In 2024 the SME segment accounted only for € 9.8 bn of new funded issuances, out of total of € 244.9 bn (Source AFME).

- In 2024, issuance of SRT transactions on SME and corporate loans accounted for € 107.5 bn out of a total of € 155.7 bn (source AFME).

- Two transactions were carried out by the BPCE Group, Aval Master FCT (June 2024) and Capitole Master FCT (December 2024).

- The ESN Task Force set up by the ECBC published in July 2024 a Blueprint, where reflections were made on certain aspects of the regulatory treatment of ESN, as well as the main characteristics of the product which need to be regulated in a specific EU legislation. In particular the success of the ESN instrument lies primarily in the bail-in exemption (as for traditional covered bonds), a dedicated RW in the prudential framework and ECB eligibility.