27 February 2024

Issuance of social bonds attracted particular attention during the peak phase of the pandemic, when a large number of (acute) measures to combat the resulting crisis – such as short-time working allowances or aid loans to SMEs – were refinanced via the issuance of social bonds. The issuance volume of social bonds in the EUR-denominated market reached a peak in 2021 of EUR 111bn. Afterwards, due to the cessation of new funding needs for the EU’s SURE program, issuance started to drop, and other socially focused investment themes have only slowly emerged. For the covered bond market, the issue of social and affordable housing is especially relevant and is set to increase in importance in the current inflationary environment, with mortgage rates increasing and real wages decreasing. Moreover, international refugee movement is growing, and this has significantly increased demand for social housing in Europe as well as for infrastructure such as public and publicly subsidized educational services or facilities that support childhood development for example. Next to social bonds, several issuers have decided to place sustainability bonds on the market. These instruments combine social and green projects and therefore extend the range of potential asset types on banks’ balance sheets. This makes it easier for smaller issuers to identify a sufficient amount of eligible assets and to reach the critical mass necessary to enter the bond market.

In the past two years, a number of newcomers have entered the social covered bond market. These programs of social bonds were mainly focused on social and affordable housing. These include, for example, 1. La Banque Postale Home Loan SFH, which refinances government’s regulated social home-ownership loans, which are granted to people with modest incomes and enable people to become homeowners by buying or building their main home, and 2. Landesbank Saar, which placed a sub-benchmark public-sector covered bond focused on public utilities, health and care, education and research.

Market overview for social/sustainability covered bonds

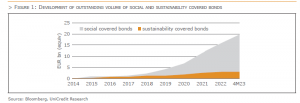

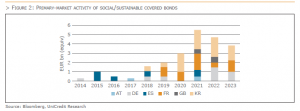

The social and sustainability covered bond emerged in 2014 with the first ESG Pfandbrief issuance with a social focus in sub-benchmark format by Muenchener Hypothekenbank. In 2015, the first social covered bond in benchmark size followed by Kutxabank. Momentum started to build in 2018 with two EUR-denominated benchmark social covered bonds and one sustainability covered bond. In 2021, a preliminary peak (in volume) was reached with eight deals and an overall volume of EUR 5.5bn (equivalent), whereas with 12 deals, 2022 proved to be most active by number of deals. In the first four month of 2023, there were ten deals with an aggregate volume of EUR 3.8bn.

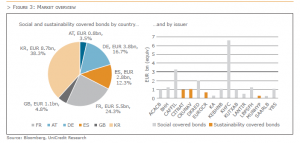

As of end-April 2023, the asset class comprised 45 social and sustainability covered bonds with an aggregated volume equivalent to EUR 22.7bn. Of these, 31 were of euro-denominated benchmark size: 26 in social and 5 in sustainability format. With respect to the number of issuers, there are currently 14 active issuers from six countries in the social and sustainability covered bond market. The first sustainability covered bond issued in 2014, by Muenchener Hypothekenbank, matured in 2019, and one social covered bond from Kommunalkredit Austria matured in 2021 (both issuers have no outstanding social covered bonds anymore).

With regard to the regional distribution of primary-market activity, an initial focus is on Europe. Nevertheless, with a total of 20 issues from three different issuers for a total volume of EUR 8.7bn, Korean banks account for the largest share of issuance by country and have strongly contributed to the growth that the market has experienced, especially since 2020. French issuers entered the market relatively late (in 2019) but now occupy second place, with a volume of EUR 5.5bn.

Purpose and usage of social and sustainability covered bonds

While social covered bonds fund projects that help to deal with a specific social issue and/or seek to achieve positive social outcomes for specific target groups, sustainability covered bonds finance both green and social projects under the same format.

In the absence of corresponding legal foundations and a social taxonomy, which is currently in the works and will probably remain so for some time to come, corresponding market standards have emerged in recent years in the form of the Social Bond Principles (SBP – current version of 2021) and the Sustainability Bond Guidelines (SBG – current version of 2021) of the International Capital Market Association (ICMA). An update of the two ICMA standards will follow in June 23. Both standards deliberately do not contain a final classification of project categories in order not to pre-empt corresponding national and international legislative initiatives.

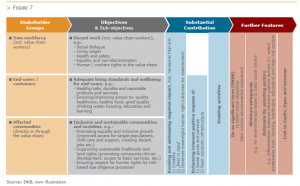

Based on the Social Bond Principles, the following six areas of application are possible, but not limited to:

In general, social projects according to the ICMA standards should be aimed at specially – but not exclusively – defined, specific population groups, which is an important element of the Social Bond Principles that might for example include people living below the poverty line, the unemployed, or vulnerable groups. The definition of these target population groups depends on local circumstances and may also include addressing the general public.

Many projects in areas like social/affordable housing or education serve social and environmental targets at the same time. The ICMA standards suggest that a classification of the proceeds as a social bond in this case should be based on the issuer’s main objectives for the underlying projects. At the same time, issuers have the opportunity to intentionally mix green and social projects in a sustainability bond program. In the covered bond space, Eurocaja Rural is an example which uses SME financing in the region Castile La Mancha for employment generation purposes as well as social housing and energy-efficient building for its sustainable covered bonds.

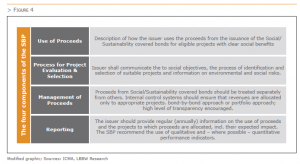

All existing social and sustainable covered bond issuance programs apply ICMA’s voluntary market standards, which focus on transparency, disclosure and reporting. As a basis for such a program, a corresponding framework should be created addressing the following four core components:

Additionally, the ICMA standards recommend that issuers have an independent third party to verify the alignment of their framework with the SBP/SBG (second party opinion). Furthermore, to facilitate the issuance of social bonds, ICMA published a “Pre-issuance Checklist for Social Bonds/Social Bond Programmes”, which aims to give guidance on the necessary steps for establishing a Social Bond Framework and to prepare issuers for reporting and common questions of the external review provider. In addition, in order to harmonize reporting practices ICMA provides principles and recommendations for reporting as well as a set of sample indicators to report on the impact of the re-financed projects. Post-issuance social bond reports should comprise an allocation reporting and an impact reporting part. While the first one in many cases looks similar to already established reporting practices from the green bond universe, the latter one differs significantly. Where the impact of green bonds is often expressed in carbon or Greenhouse gas (GHG) avoided, social projects know a wider range of potential impact parameters, and new social bond issuers should take the opportunity to discuss with investors prior to inaugural publication what is most useful for the investors’ own reporting requirements. With regards to social/affordable housing projects, the number of affordable housing units financed, the average rent of financed units vs. a material benchmark, and the number of beneficiaries are among investors’ most looked-after impact-metrics.

In June 2022, the social bond principles were supplemented by an Annex 1 which, among other things, provides for a distinction between “Standard Social Use of Proceeds Bonds” and “Secured Social Bonds” – e.g. Social Covered Bonds. Covered bonds can carry the social label if the funds raised are used to finance or refinance social projects that (1) directly collateralize the bonds (“Secured Social Collateral Bonds”) or (2) are not necessarily part of the cover pool (“Secured Social Standard Bonds”). The first ones apply an intrinsic principle of all covered bonds to the social bond world: The cover principle. Under the Association of German Pfandbrief Banks’ (vdp) Minimum Standards for Social Pfandbriefe only this version is possible. In contrast, the latter ones enable a break between the cover pool and the social projects to be financed: Covered Bonds can be labeled as “social”, despite a collateralization which is not (only) provided by social assets, allowing issuers a wider range to use the bonds’ proceeds. For covered bond creditors, the distinction between the two bond types may imply different market risks in the event of insolvency, assuming better recoverability of “sustainable” projects. For investors it is advisable to look at the fine print. According to ICMA, it should be clear to investors what format of social covered bond they invest in. Issuers can support them to declare explicitly their chosen format in their Social Bond Frameworks.

A look at the market shows that in contrast to the wide range of theoretically possible use of proceeds, current social and sustainability covered bond issuers focus primarily on area of affordable housing (SDGs 10 and 11). 2/3 of the outstanding issuance volume is allocated to affordable housing. But there are special cases like CAFFIL, where healthcare is in the center of the use of proceeds (SDG 3). In total, healthcare represents 16% of the outstanding volume. The third largest category of project allocation is basic infrastructure, which is represented by DKB and its covered bonds with focus on clean water and sanitation (SDG 6).

Pricing advantages

Social and sustainability covered bonds have the same high security standards and risk profiles as ordinary covered bonds. Thus, there should be no significant price difference among comparable covered bonds as is currently the case. However, potential (minimal) differences could arise from social and sustainability covered bonds’ broader investor base and the implied higher demand for social and sustainability covered bonds.

With respect to relative value, it is challenging to analyze the existence of a premium for social and sustainability covered bonds compared to ordinary covered bonds. First of all, the spread landscape of covered bonds is overall compressed and thus offers limited scope for differentiation. In addition, most issuers do not have covered bonds with a comparable tenor outstanding in both social or sustainability covered bonds and in ordinary covered bonds. French issuer CAFFIL offers the most suitable example, and as the chart below indicates, there is no visible difference between adjacent bonds. With respect to primary-market performance, data show that ESG-labelled covered bonds benefit from larger order books and higher cover ratios compared to conventional covered bonds. However, data on new issue premiums are ambiguous. In 2022, the new-issue premium of ESG-labelled covered bonds was, on average, 0.4bp lower, while in the first months of 2023, it has been higher by the same difference. Accordingly, data suggest that the pricing advantage of an ESG label is minimal to nonexistent for covered bond issuers – but the larger order books reduce execution risk and might support more-stable secondary-market performance, as ESG investors have been deemed more sticky.

By Julian Kreipl, UniCredit & Sabrina Miehs, Helaba & Rodger Rinke, LBBW & Bodo Winkler-Viti, BerlinHyp