29 November 2022

Green bond principles and use of proceeds

The market for green bonds has grown steadily, reaching a total outstanding volume of EUR 1,128 bn (worldwide in EUR equivalents), which accounts for the lion’s share of the total ESG bond market, at the end of last year, with further growth expected. After a record new issue volume of green bonds of EUR 469 bn in 2021, the total volume of new issues in the first six months of 2022 has been EUR 288 bn. The volume of newly issued green covered bonds (EUR equivalents, all currencies) after six months amounted to EUR 12 bn. After the first green covered bond issue in April 2015, many issuers followed suit. As at the end of June 54 banks (thereof 28 in the EUR benchmark segment) have been active in the green covered bond segment. They issue mainly in EUR, followed by DKK and SEK. In the EUR (sub-) benchmark segment, a total of EUR 51.25 bn in sustainable covered bonds were outstanding at the end of the first half of 2022. Of these, EUR 34.55 bn were green covered bonds, EUR 13.9 bn social covered bonds and EUR 2.8 bn sustainable covered bonds.

Basically, green covered bonds raise funds that are used to refinance green properties with three exceptions. Two issuers refinance public assets with a green covered bond and another issuer has refinanced renewable energy loans with its sub-benchmark size green covered bond. All other issuers use green covered bonds to finance both residential and commercial real estate assets that meet certain sustainability criteria. The EU has been working on a green bond standard (GBS) since 2019 and the EU Commission published a proposal on 6 July 2021. In May 2022, the EU Parliament agreed on a common position. This is followed by a trialogue between the European Commission, the EU Council and the EU Parliament.

In the absence of corresponding legal foundations, corresponding market standards have emerged in recent years in the form of the Green Bond Principles (GBP) of the International Capital Market Association (ICMA), which were published in a revised version on 10 June 2021. The standard confirms the previous recommendations and further increases the issue of transparency.

In particular, it recommends a transparent presentation of the climate transition strategy in the green bond framework as well as the alignment with the GBP. In addition, ICMA recommends that issuers appoint an external review provider to confirm compliance with the GBP pre and post issuances. The principles deliberately do not contain a conclusive classification of project categories in order not to pre-empt corresponding national and international legislative initiatives.

The Green Bond Principles define the following five key environmental areas of action:

Based on these five areas, the guidelines name numerous possible project directions, but do not limit them. With regard to covered bonds, we concentrate on the following:

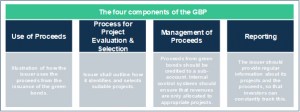

Most issuance programmes apply these voluntary market standards, which focus on transparency, disclosure and reporting. As a basis for a green issuance programme, a corresponding framework should be created that addresses the following four core components:

Source: ICMA, LBBW Research

Additionally, it is recommended that issuers have an independent third party verify the alignment of their framework with the GBP (second party opinion). Furthermore, ICMA has published a reference framework that helps issuers and investors map the investment targets of the respective green emission programme to the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). A detailed analysis of the green covered bond programmes of the big issuers with benchmark formats in regard to the SDG targets shows that the following are used most frequently:

Source: UN SDG

In contrast to the wide range of theoretically possible SDGs, current green covered bond issuers focus primarily on the goal of Sustainable Cities and Communities (SDG 11). But there are some special cases where Clean Water and Sanitation as well as Responsible Consumption and Production are in the centre of the use of proceeds (SDG 6 and 12) for a public sector covered bond. Other covered bonds focus on Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure (SDG 9).

For large banking groups, the Green Bond Framework and the SPO refer to the entire range of green activities and their refinancing. Considerations for the use of proceeds includes all green loans, whether they are cover pool eligible or not. The part that is refinanced via covered bonds is only a subset. The assets must comply with the respective legal requirements, which in the case of green covered bonds concerns real estate financing almost exclusively. In the case of pure-play mortgage banks, the use of proceeds is limited to mortgages from the outset.

The prerequisites for further growth in the market for green covered bonds are the availability of a corresponding collateral pool as well as the willingness of issuers to use this basic volume of green loans for covered bond issues. However, whether these banks use their green loan portfolios for covered bond issues or prefer green senior issues, for example, may depend on the achievable pricing advantage of a covered bond issue with “green” status. In view of the current high market volatility, we see certain advantages for covered bonds as a refinancing instrument. Based on the immense volume of mortgages refinanced via covered bonds, there is a high potential for green bonds in the medium to long term in our view. This should also receive strong support from the political level, since the European Green Deal is driving the sustainable renewal of real estate portfolios in Europe. However, there is still the next hurdle to overcome: The EU taxonomy. While ICMA deliberately does not make a final classification of project categories, this is done in the taxonomy. Furthermore, the future EU green bond standard is directly linked to the requirements of the EU taxonomy.

The EU taxonomy regulation in a nutshell

The EU taxonomy regulation came into force in July 2020 and provides a unified classification system for sustainable activities. Together with China’s taxonomy it is also one of the reference pillars for the work of the International Platform on Sustainable Finance (IPSF) on the common ground taxonomy.

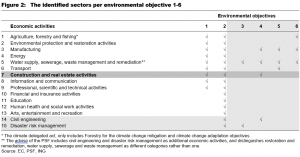

At this point, the EU taxonomy identifies six environmental objectives. However, its scope may be extended in the coming years with social objectives, as well as by economic activities that significantly harm the environment, or do not significantly impact the environment.

An economic activity is considered environmentally sustainable and thus EU taxonomy aligned if it:

In June 2021, the European Commission adopted the climate delegated act setting the technical screening criteria for the climate change mitigation and climate change adaptation objectives (1-2) and the conditions for avoiding significant harm to the other environmental objectives (including 3-6). These criteria became applicable on 1 January 2022. The environmental delegated act for the remaining four environmental objectives is expected to be published in 2022 (to become applicable on 1 January 2023).

Within the climate delegated act nine sectors are identified for the climate change mitigation objective based on their emissions footprint, while 13 sectors are distinguished for the climate change adaptation objective. In March 2022, the Platform on Sustainable Finance (PSF) published its advice on the technical screening criteria for the other four environmental objectives, building further on the sectors identified in the climate delegated act (see figure 2).

Building loans contributing substantially to climate change mitigation

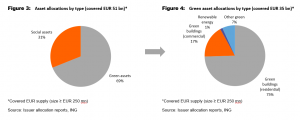

Due to the traditional dominance of mortgage assets in covered bond collateral pools, the technical screening criteria for construction and real estate activities are the most relevant for green covered bonds. This is illustrated in figures 3 and 4, which confirm that of the 69% in EUR sustainable covered bond green asset allocations, 92% finance energy-efficient building loans.

The delegated act divides the construction and real estate sector into seven sub-sectors. Two of these are low-carbon activities that themselves contribute substantially to one of the taxonomy’s environmental objectives. These are generally the most important for the selection of green real estate assets:

One is a transitional activity:

The remaining four activities are all enabling activities. These include the installation, maintenance and repair of:

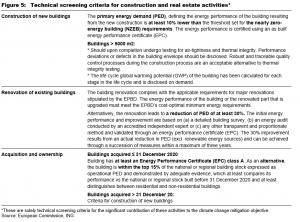

Figure 5 gives an overview of the technical screening criteria for substantial contribution to the climate change mitigation objective for the first three real estate activities. To be taxonomy compliant, buildings built as of 2021 should have a primary energy demand (PED) that is 10% lower than the country specific thresholds for ‘nearly zero-energy buildings’ (NZEB) applicable for new buildings in the EU per 2021. Buildings built before 31 December 2020 should have an energy performance certificate (EPC) class A. These buildings are also taxonomy compliant if they belong to the top 15% most energy efficient buildings of the regional and national building stock built before 2021.

The 15% best in class criterion for buildings built before 2021 is probably most crucial for the ability of banks to issue green covered bonds that solely (re)finance taxonomy aligned real estate loans. After all, the portion of buildings labelled with an A class EPC certificate is typically small in most jurisdictions. Besides, these labels often lack comparability. As a result, a building can be labelled A in one country, while in another country with stricter EPC criteria a similar type of building could be labelled B or C. In some countries EPC labels may not even comprise a rating classification. The comparability issue may improve with the planned revisions to the Energy Performance and Buildings Directive (EPDB) as discussed later in this article.

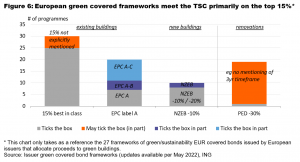

Figure 6 shows that most sustainability bond frameworks of European covered bond issuers use the top 15% selection criterion for green building assets. There are only a few that do not explicitly confirm that the selection norms applied have a 15% best in class outcome for all the building loans collected. Besides, sustainability bond frameworks increasingly seek compliance with the EPC label A criterion. That said, thanks to the 15% best in class alternative, they don’t have to limit the use of EPC labels to class A, as long as proper evidence is provided that the selected property loans represent the 15% most energy efficient building assets.

Not all issuers include renovation loans in their green asset portfolios. Those that do, refer to a 30% improvement in energy performance, but generally without additional requirements, such as the TSC’s three-year maximum term for a series of measures to achieve the upgrade. Thus far, still few issuers have introduced the NZEB-10% criterion for buildings built per 2021. We believe however, that frameworks will continue to be updated to ensure optimal taxonomy compliance of green portfolios.

However, meeting the technical screening criteria is not the only challenge issuers face when ensuring taxonomy alignment of their green bonds. Even if an economic activity contributes significantly to the climate change mitigation objective, it still has to avoid doing significant harm to any of the other environmental objectives. To name an example, the generic DNSH criteria for climate change adaptation therefore require a climate risk and vulnerability assessment (CRVA) to identify physical climate risks such as wildfires or floods, and an adaptation solutions plan to reduce these risks.

The importance of taxonomy compliance for green covered bonds

Banks have good reasons to strive for the best possible taxonomy alignment of their green assets. These stretch well beyond the purpose of green bond issuance alone. The taxonomy regulation will be an important pillar to the future voluntary EU green bond standard, which according to the draft proposals will require full taxonomy alignment of the use of proceeds.

However, it also forms an integral part of EU regulation promoting sustainable reporting, such as the sustainable finance disclosure regulation (SFDR) and non-financial reporting directive (NFDR), as revised and expanded via the corporate sustainability disclosures regulation (CSRD). These disclosure regulations have the consequential side-effect that companies (including banks) will face increased investor scrutiny on the sustainability of their activities, among others from portfolio managers that have to show to what extent their investment funds and portfolios consider sustainability aspects. The taxonomy compliance of the assets financed via green (covered) bonds is just the tip of the iceberg.

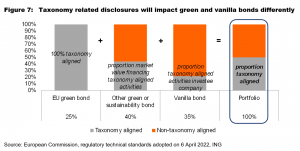

For taxonomy disclosure purposes, the SFDR, NFRD (CSRD) and the future EU green bond standard will in a way work as communicating vessels. This point is illustrated by the indicative investment portfolio comprised of bonds in figure 7. The graphic takes the regulatory technical standards on disclosures under the SFDR, adopted by the European Commission on 6 April 2022, as a reference. These disclosure technicalities should apply from 1 January 2023 to financial market participants such as insurance companies, pension funds, investment firms, or credit institutions that provide portfolio management services.

The key performance indicator (KPI) measuring the taxonomy compliance of financial products, is calculated as the ratio of the market value of all investments of the financial product in environmentally sustainable (ie taxonomy aligned) activities versus the market value of all investments of the financial product. Environmentally sustainable investments can (among others) include the following:

For financial companies such as banks, this proportion comes down to the share of environmentally sustainable economic activities as disclosed under the NFRD (CSRD) (ie, “green asset ratio”).

This illustrates that the taxonomy-related disclosure requirements may impact all bonds issued, whether marketed with a sustainable use of proceeds or not. The taxonomy compliance of vanilla bonds will also be considered via the share of activities of the issuer that are deemed to be environmentally sustainable. Hence, issuers reporting a stronger taxonomy alignment under the NFRD (CSRD) could see this translate into more favourable trading levels, also for their vanilla bonds.

The intentions of the ECB to introduce climate change related disclosure requirements for collateral, may only strengthen this effect. As of 2026 the central bank will solely accept as collateral marketable assets and credit claims from companies and debtors that comply with the CSRD. In light thereof, the ECB would support better and harmonised disclosures of climate related data for assets, such as covered bonds and asset-backed securities, that do not fall under the CSRD.

The European green bond standard

Meanwhile, fixed income investors will likely favour those instruments that meet all the criteria of the future EU green bond standard, as these bonds are considered to be 100% taxonomy aligned. It is important to bear in mind however that the EU green bond standard proposals of July 2021 take a use of proceeds approach. For green covered bonds aiming to comply with the EU green bond standard this means that bond proceeds should solely be allocated to (new and/or existing) loans that finance environmentally sustainable economic activities (ie are taxonomy aligned). These loans are not explicitly required to be part of the cover pool.

Besides, under the European green bond standard proposals environmentally sustainable activities do not yet have to be fully taxonomy aligned upon issuance, as long as there is a taxonomy alignment plan in place ensuring that the taxonomy requirements will be met within a period of five years (or ten years at most if justified). Nonetheless, proceeds always have to be allocated in full before the bond matures. If the technical screening criteria and do no significant harm provisions are amended, issuers also have to make sure the green bond proceeds are (re)allocated to conform to the new criteria within a period of five years. Otherwise they can no longer claim that the bond is a European green bond. This five year period may still be removed or increased as part of the Trilogue discussions on the EU green bond standard (ongoing at the time of writing).

Due to the use of proceeds approach there are for covered bonds no information requirements on the taxonomy alignment metrics at the level of the cover pool. The transparency requirements for European green bonds, such as the (pre-issuance) green bond factsheet and (post-issuance) allocation and impact reports, will only provide information on the level of the green asset portfolio.

Having said all that, we do believe that most issuers will strive to confirm they have sufficient taxonomy compliant assets in the cover pool against their outstanding European green covered bonds. After all, particularly where taxonomy aligned assets would have lower probabilities of default, green covered bond investors may have a preference for proceed allocations to taxonomy compliant assets that are in fact also part of the cover pool. This despite the pari passu preferential claim to those assets with vanilla covered bondholders. However, the taxonomy alignment of the green covered bond will probably still be viewed as most important by investors when it comes to buying a European green covered bond.

This does not mean that green bonds that are not fully taxonomy compliant will lose investor interest. They will still count towards the taxonomy KPIs for the part that they do finance taxonomy compliant activities. The EU green bond standard may nonetheless become the preferred reference for investors by which issuers can show the taxonomy alignment of their green bonds. Especially as investors may not always have the resources or the willingness to perform a full taxonomy compliance assessment themselves for every green bond. Against this backdrop, industry initiatives, such as the EMF-ECBC’s Energy Efficient Mortgages Initiative (EEMI) and the VDP’s minimum standards for Green Pfandbriefe, will remain an important support to both issuers and investors in their green bond structuring and investment processes.

EPBD revisions will enhance the energy efficiency of buildings

When it comes to the future evolution of the environmental metrics of covered bond collateral pools, it is also important to bear in mind that the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD) is aiming for a zero-emission building stock by 2050. The measures included in the legislative proposal 2021 are considered proportionate and build to the largest extent on the existing design of the original 2002 Directive and the 2010 and 2018 revisions. As already indicated in the Climate Action Plan, the EPBD is the key legislative instrument to deliver on the 2030 and 2050 decarbonisation objectives. It follows up on key components of the three focus areas of the Renovation Wave Strategy, including the intention to propose mandatory minimum energy performance standards, following an impact assessment looking at their scope, timeline, phasing in and accompanying support policies.

In the EU, heating, cooling and domestic hot water account for 80% of the energy that households consume. In order to make Europe more resilient there is a need for energy efficiency renovation for buildings and making them less dependent on fossil fuels. Energy efficient buildings are key for reducing the energy consumption, for bringing down emissions and for reducing energy bills since buildings account for 40% of energy consumed and 36% of energy-related direct and indirect greenhouse gas emissions.

The EPBD´s main targets are reducing buildings’ greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and final energy consumption by 2030 and setting buildings towards EU-wide climate neutrality in 2050. The EPBD is grounded in several specific objectives: to increase the rate and depth of buildings renovations, to improve information on energy performance and sustainability of buildings, and to ensure that all buildings will be aligned with the 2050 climate neutrality requirements.

Zero-emission buildings become the new standard for new buildings, the level to be attained by a deep renovation as of 2030 and the vision for the building stock in 2050. When discussing energy performance it always comes back to data, more precisely the lack of data. Member States shall set up national databases for energy performance certificates of buildings, which also allow to gather data related to building renovation passports and smart readiness indicators. Information from the national databases shall be transferred to the Building Stock Observatory, based on a template to be developed by the Commission. The EPBD also improves the already existing provisions on energy performance certificates, their issuing and display, and their databases. To ensure comparability across the Union, by 2025 all energy performance certificates must be based on a harmonised scale of energy performance classes, in which the best class A represents a zero-emission building, while the lowest class G shall include the 15% worst-performing buildings in the national building stock. Furthermore, the European Commission proposals require non-residential buildings to have an EPC label of at least F by 2027, and residential buildings by 2030. Non-residential and residential buildings should have an EPC label of at least E by 2030 and 2033 respectively. Although the EPBD will widen the need for EPC, it has to be noted that there are many building owners that do not have a mortgage or are “off the market” because they just live in their house. Therefore we welcome the EU Save Energy Plan of 18 May 2022 not only because it seeks to make Europe more resilient but because it focuses efforts on meeting the targets to reduce energy consumption as a whole.

The EU Save Energy Plan

On 18 May 2022, the European Commission unveiled its new EU Save Energy Plan. This latest scheme was launched in concert with the wide-reaching REPowerEU plan, which aims to transform the EU’s energy system amid the current geopolitical and commodity market uncertainties, moving away from fossil fuel sources and further supporting renewable energy technologies.

In terms of the specific content of the EU Save Energy Plan, the European Commission addresses the issue of energy efficiency by way of two approaches:

These will be underpinned by both a financial framework and a governance structure.

The energy efficiency of buildings is one of the key pieces of the plan, as the Commission proposes specific actions that involve both Energy Efficiency Directive and the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive. Particularly, the body proposes:

The European Commission also seeks to increase private financing of energy efficiency. To this end, it proposes to launch, in cooperation with Member States, a high-level European Energy Efficiency Financing Coalition with the financial sector, based on the Energy Efficiency Financial Institutions Group (EEFIG) and to examine possible supplementary measures to trigger further private investments, for instance, through mortgage portfolio standards or pay-for-performance schemes.

Green covered bond market

The significant impact that COVID-19 had on markets and funding is just fading out, as the next market turmoil in form of the Russia-Ukraine crisis and rising inflation risks as well as rising yield curves are impacting financial markets. But the current market environment is supporting covered bond issuance as fading ECB support and high volatility are favoring stable safe-haven products like the covered bond and by May 2022 issuance was already approaching the total supply volume of covered bonds in FY2021. Together with the increased issuance of covered bonds, we also see several new green covered bond issues. We anticipate that the positive trend to make increased use of green covered bonds will persist, especially when keeping in mind the newly introduced EU taxonomy and the EU’s climate targets of reducing GHG by 55% until 2030. The buildings sector is the largest energy consuming sector and responsible for about 40% of energy consumption and 36% of carbon emission in the EU – and covered bonds are the most widespread tool to refinance mortgages. Aside from the sustainable perspective, issuers as well as investors are looking at pricing and performance differences of green and non-green covered bonds.

Green covered bonds and non-green covered bonds have the same risk profiles from a credit risk perspective. For this reason, they should not display significant pricing differences, as is currently the case. Potential (minimal) differences are, in our view, likely attributable to liquidity, the amount of time that has elapsed since issuance, amounts outstanding, etc. However, there does seem to be one difference: the investor bases of green covered bonds are broader than those of non-green covered bonds. In addition to attracting the attention of traditional covered bond investors, green covered bonds also attract the interest of dedicated ESG investors. This broader investor base could facilitate the placement of new deals in times of crisis, but during the COVID-19 sell-off in early 2020 and also during the phase of increased volatility due to geopolitical circumstances and inflation risks since February 2022, no spread-supportive impact could be observed.

We start by considering the issuers’ viewpoint and examine whether green covered bonds achieve beneficial pricing. Beneficial pricing would be justified given the costs associated with setting up a green bond framework, the additional documentation and reporting involved as well as the external assessment required (in the form of a second-party opinion). Available deal data on new issues confirm the common assumption that green deals attract a broader investor base and involve more different accounts and accordingly this should pave the way for advantageous new issue premiums (NIP) and higher cover ratios for new deals. For 2021, green covered bonds enjoyed a volume-weighted average NIP of 0.6bp (2020: 0.8bp) versus 0.9bp (2020: 3.0bp) for traditional covered bonds and volume-weighted average cover ratios of 2.2 times (2020: 3.2 times) versus 2.0 times (2020: 2.3 times) for traditional covered bonds. Although differences have been smaller last year, the demand for green covered bonds is still higher and NIPs are lower, which leads to a calculative funding advantage for issuers.

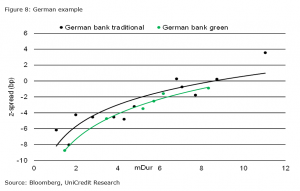

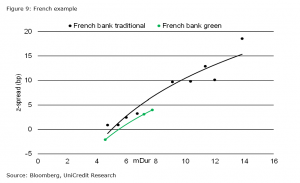

Studying current market snapshots to see how pricing occurs in secondary markets does not offer a clear picture. The following two charts show examples of Z-spread levels of two of the most active green covered bond issuers, which also have solid secondary curves with traditional covered bonds. Taking a German green covered bond issuer as an example, both the traditional and the green curve are indicating a small 1bp greenium, while comparing single bonds to each other results in a negligible difference of less than 1bp (see figure 8). In figure 9, the green covered bonds from a French issuer are compared with its traditional covered bonds. In this case, the lower green curve suggests a greenium of 1-2bp, while comparing the two closest bonds with a remaining term of 7Y results only in a greenium of 0.3bp – which is again negligible in our opinion and might result from other factors. Lastly, we cannot determine a market-wide greenium for green covered bonds which might be explained by already tight spread levels and hence limited room for further tightening as well as reduced liquidity in the market as the ECB has absorbed large parts of the segment. Nevertheless, in both showcases, the green covered bonds are trading at (very) small premiums to comparable bonds from the same issuer.

For now, we expect the greeniums to stay low, but looking forward and factoring in increased ESG bond supply and increased investor interest, we consider a greenium of 1-2bp as possible.

Performance

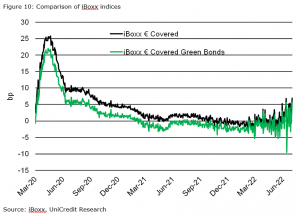

From an investor’s point of view, investing in green covered bonds yields not only financial but also environmental returns – but does responsible investing have an influence on performance? As can be seen in figure 10, both the iBoxx EUR Covered index and iBoxx EUR Green Covered index are very closely correlated. Since 2020, the green covered bond index has been trading within a range of -5.1bp and -0.6bp to the overall iBoxx EUR Covered index, while the average duration was 1.3 year longer, and of course a completely different issuer and country composition. At what is considered the peak of the COVID-19 crisis (in spread terms) in mid-April 2020, the average spread of the two indices increased from around 3bp to 4bp and the spread difference peaked in early-May 2020 at 5.1bp, while it declined in the subsequent recovery phase until end-June 2020 to 3.5bp. Since then, the spread difference kept further declining to an average of 1.3bp in 2022. In our view, these small differences in indices are attributable to index composition, liquidity, time that has elapsed since issuance, outstanding amount, duration, etc.

Conclusion.

By the end of June 2022 the global market for EUR sustainable covered bonds had grown to EUR 51.25 bn, with green covered bonds making up 67% of the total amount in ESG covered bonds outstanding. While green issuance volumes in covered bonds remain relatively modest compared to the senior unsecured market, the substantial volumes of mortgages refinanced via covered bonds do offer good potential for the green covered bond market to further expand in the medium to long term. This growth is supported by political and regulatory developments in Europe, aiming at channeling investments towards environmentally sustainable assets. The taxonomy regulation, and related voluntary EU green bond standard, in particular, will form a key reference point for investors when assessing the contribution of green covered bonds towards environmentally sustainable objectives. The demand from investors for assets meeting the criteria from the taxonomy regulation will likely support a wider spread differential between green and non-green covered bonds than witnessed today, particularly for green covered bonds able to demonstrate full taxonomy alignment. Meanwhile, regulatory developments aiming at improving the energy performance of buildings will be crucial to the general upgrading of the ESG metrics of building loans on bank balance sheets, including of those present in covered bond collateral pools.

By Maureen Schuller, ING, Alexandra Schadow, LBBW, Julian Kreipl, UniCredit and Sanna Eriksson, OP Mortgage Bank